It sounds like something from a horror flick. A small, parasitic creature swims into the mouth of a fish and attaches itself to the organism’s tongue — yes, fish have tongues — causing it to slowly degrade before latching onto the stub leftover, thus becoming a parasitic pseudo tongue. Over time, the host loses its ability to eat and slowly succumbs to starvation.

So claims a now-viral Instagram post that was shared in March 2021 by the Smithsonian Institute in appreciation of #ParasiteWeek2021. And if the photo was enough to give you the heebie-jeebies, then you may not want to continue reading. Because both the photograph in question and the supposed parasite featured in it are, in fact, real.

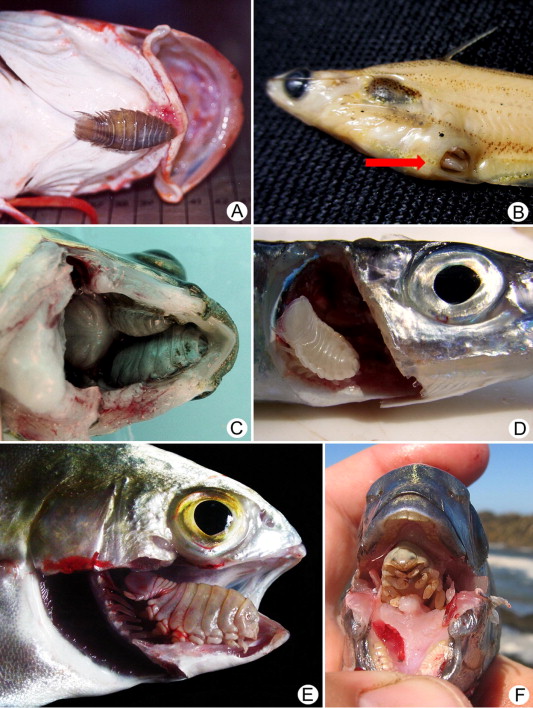

The picture featured an organism known as a cymothoid isopod and was originally shared on Aug. 3, 2020, by marine biologist Jimmy Bernot, a post-doctoral scholar with the National Science Foundation and Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History specializing in crustacean phylogeny and parasite evolution. In an email to Snopes, Bernot said that he captured the photo during a 2016 survey of fish parasites of Moreton Bay, Australia.

The host fish is known scientifically as Mugil cephalus or the Flathead mullet.

"Not to be confused with the business in the front, party in the back haircut," said Bernot.

And the parasite seen inside the mullet's mouth is what is known as a cymothoid isopod that measured about an inch long. According to the scientist, it appeared that the fish did use the creepy-crawly as a "pseudo tongue."

The fact that you can see imprints of the fish's teeth on the back of the isopod indicates the fish is crushing items against the isopod similar to how the fish would use its tongue, he said.

Isopods are marine invertebrates, or animals without backbones, that belong to a greater group of animals called crustaceans. Only a handful of the at least 95 known families of isopods are parasitic, one of which being cymothoid, according to research published in a 2014 issue of the International Journal for Parasitology: Parasites and Wildlife. The cymothoidae family in particular is made up of 350 species of aquatic parasitic isopods. Widely distributed around the world in both oceanic and freshwater habitats, cymothoids are on the larger side of parasites and can reach lengths upwards of a quarter of an inch, with the largest reaching lengths of up to 3 inches.

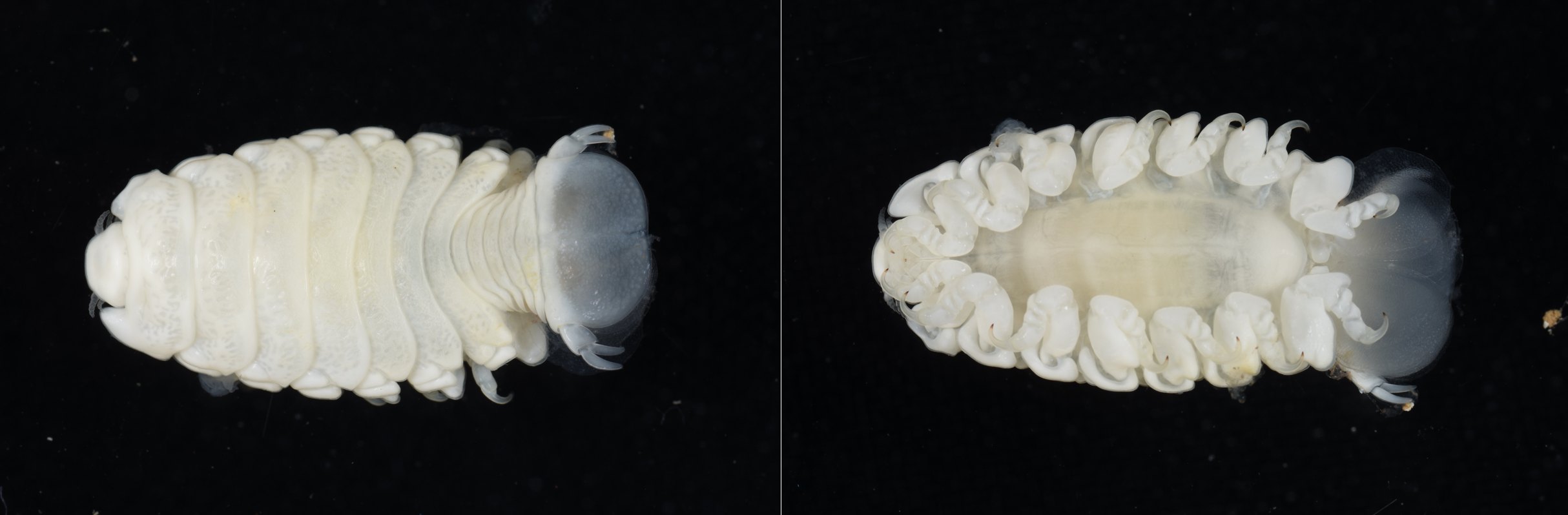

"Cymothoids superficially look like free-living isopods, such as terrestrial rolly-pollies or pillbugs that people may be familiar with, except for their powerful hooked legs that they use to attach to their host," explained Bernot. "As adults, they are not good swimmers and typically stay permanently attached to their host."

Equipped with a long, slender body that tapers at the end and sharply curved hooks at the end of its limbs, the cymothoid can attach to its host fish at the gills or mouth as well as externally or inside the host flesh, depending on the species. Cymothoids are generally host-specific, meaning each cymothoid typically attaches to a single host species or a small group of related fish. On a parasitized fish, Bernot said that there will often be a single large female and a few small males attached nearby on the same fish.

Only a few species attach specifically to the tongue, and these are commonly called "tongue-biters." Other species attach to the skin or gills, but all have detrimental effects on their hosts including blood loss due to the parasite feeding, skin and tissue damage, deformities, and overall stunted growth and reproductive issues.

And when it comes to the cymothoid featured on social media posts, the Smithsonian Institute wrote that the “crustaceans sever the host fish’s tongue" — a claim that is only partly true.

"The cymothoids feed on blood and perhaps some of the tongue and surrounding tissue in the host's mouth, but the loss and degradation of the tongue are at least partially, if not mostly, due to atrophy of the tongue from mechanical damage caused by the strong, hooked legs that the isopod uses to attach to the base of the tongue," said Bernot. In short, cymothoids do not snip straight through the tongue of the fish, but rather cause such damage that a portion of the tongue can eventually fall off.

And according to the research institution, Bernot's photograph is the only known instance in the animal kingdom where a parasite has been observed as fully replacing its host’s organ. In a reply to his original post, Bernot said that the pictured cymothoid isopod holding caused its host to atrophy — a fancy word for wasting away.

Studying parasites like cymothoids helps researchers to better understand evolutionary biology and the unique adaptations that individual species obtain in order to survive.

"It appears different groups of parasitic isopods have independently evolved strongly clawed legs through a process called convergent evolution," said Bernot. "Convergent evolution is of interest to evolutionary biologists and developmental biologists since it gives us insights into how evolution can shape the morphology of animals."

And cymothoids also impact human health and economies because of their effect on fish, which Bernot said could sometimes infect more than 90% of fish on a single farm, including commercially farmed sea bass, bream, and salmon. As gross as it may sound, eating a fish with a parasite is "definitely still safe for humans," but the fish might be smaller or have scars, and Bernot said that means it can't be sold at its highest market value.