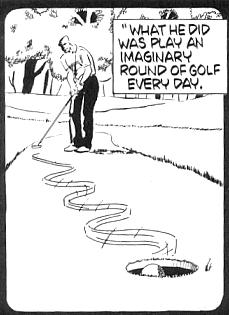

Claim: A prisoner of war who played an imaginary round of golf in his mind each day of his captivity found upon his release that he'd markedly improved his game.

Example: [Collected via e-mail, 2004]

Does anyone know the story of the prisoner of war in Vietnam who spent

Origins: This

legend about the serviceman who maintained his sanity during the many years he spent as a prisoner of war in Vietnam by playing a mental game of golf every day has long been a favorite of motivational speakers. We found it in a 1975 book authored by

Zig Ziglar, and one fellow we know swears he heard the tale around that same time at a Denis Waitley seminar. It has since appeared in the 1995 book A

In each telling we have so far examined, the imprisoned serviceman is held by his Vietnamese captors for a specified number of years (most often seven, but sometimes five). The variation in the legend occurs in the impressive results achieved by the former POW his first time back on the course:

- He plays the best round of his life (sometimes described as shooting a 74 despite a previous best in the low 90s; sometimes described as "knocking

20 strokes off his average"). - He pockets a hole-in-one off the first tee.

- He wins a golf tournament.

However the happy outcome is expressed (best game, wins the tournament, hole-in-one), the message is clear: the player's many years of unrelenting focus upon the merely imagined translates to actual success. Rather than losing his grasp of reality to the mental and physical horrors of being trapped in a hell hole, the captive keeps himself together by putting his imagination to work for him, this process resulting in the unexpected byproduct of an improved golf game. Through the example of his story, the world is supposed to gain a valuable lesson about the power the mind has to influence the outcome of that which is attempted.

Zig Ziglar described the pitfalls and rewards of visualization thus:

As we delve into our self-image, let's remember that the mind completes whatever picture we put in it. For example, a plank

In his groundbreaking 1980 book In Pursuit of Excellence, sports psychologist Terry Orlick stressed the importance of visualization, saying, "Athletes who make the fastest progress and those who ultimately become their best make extensive use of performance imagery."

He described the case of an Olympic figure skater stymied in her attempts to master a particular skill. After working with her to get her to mentally see herself completing the move flawlessly, the skater began to have success with that skill during her practices, and within two weeks of their first session was performing the skill "with more quality and with more consistency than she had ever done it."

Former Olympic springboard diving champion Sylvie Bernier would mentally practice her dives (all ten of them) each night before going to sleep.

"As I continued to work at it, I got to the point where I could feel myself on the board doing a perfect dive and hear the crowd yelling at the Olympics," she said. I worked at it so much, I got to the point that I could do all my dives easily."

Orlick speaks of training the mind and body to execute skills to perfection by programing a high quality performance into the athlete's brain. While it might sound like psychological mumbo-jumbo, visualization has taken its place as one of the key components

of what goes into turning a skilled athlete into a champion, supplementing inherent skill, expert coaching, and training regimens specifically geared to bringing the athlete to a performance peak at exactly the right time.

Although many current versions of this legend identify one "Major James Nesmeth" as the Vietnam POW whose playing golf in his mind translated to his becoming a far improved linkster once he was back home, we have been unable to verify that anyone of that name served in Vietnam, was held as a POW, was released from captivity, or achieved notable results on the links after returning to the U.S. Nonetheless, the legend's underlying message that visualization can help to dramatically improve one's performance is true, although — unlike the legend's expression of this truth — visualization works in combination with other performance-enhancing factors, not as a substitute for them. Ergo, if you want to improve an area of your personal performance (sports-related or otherwise), do picture yourself a winner, but also continue to supply the other inputs as well.

Barbara "daydream believer" Mikkelson

Last updated: 29 March 2015

Sources: |

Brunvand, Jan Harold. The Baby Train. New York: W. W. Norton, 1993. ISBN 0-393-31208-9 (pp. 204-205). Canfield, Jack and Mark Victor Hansen [editors]. "18 Holes in His Mind." In A 2nd Helping of Chicken Soup for the Soul. Deerfield Beach, FL: Health Communications, 1995 (p. 235). Orlick, Terry. In Pursuit of Excellence. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 1980. ISBN 0-7360-3186-3 (pp. 108-111). Ziglar, Zig. See You at the Top. Gretna, LA: Pelican, 1975. ISBN 0-88289-126-X (pp. 48, 192-193).

Also told in: |

The Big Book of Urban Legends. New York: Paradox Press, 1994. ISBN 1-56389-165-4 (p. 186).